1 Augustinus, in

den Confessiones || the

Confessions

I/8:

cum || Cum

(majores homines) appellabant rem aliquam, et cum secundum eam

vocem corpus ad aliquid movebant, videbam, et tenebam hoc ab eis

vocari rem illam, quod sonabant, cum eam vellent ostendere.

Hoc autem eos velle ex motu corporis aperiebatur:

tamquam verbis naturalibus omnium gentium, quae fiunt vultu et nutu

oculorum, ceterorumque membrorum actu, et sonitu vocis indicante

affectionem animi in petendis, habendis, rejiciendis,

faciendisve

rebus. Ita verba in variis sententiis locis suis posita,

et crebro audita, quarum rerum signa essent, paulatim colligebam,

measque jam voluntates, edomito in eis signis ore, per haec

enuntiabam. 1

In these words we have || get – it seems to me – || In these words we are given, it seems to me, a definite picture of the nature of human language. Namely this: the words of the language designate || name objects – sentences are combinations of such designations || names. In this picture of human language we find the root of the idea: every word has a meaning. This meaning is correlated to the word. It is the object which the word stands for. Augustine however does not speak of a distinction between parts of speech. Whoever || Anyone who describes the learning of language in this way || If one describes the learning of language in this way, one thinks – I should imagine – primarily of substantives, like “table”, “chair”, “bread” and the names of persons; and of the other parts of speech as something that will work || come out all right. || eventually. |

Consider

now this application of language: I send someone

shopping. I give him a slip of paper, on which

are the marks || I have written the

signs: “five red apples”.

He takes it to the grocer; the grocer opens the

box || drawer that

has the mark || sign

“apples” on it; then he looks up the

word “red” in a table, and finds opposite it a

coloured square; he now

speaks || pronounces || says out loud the series of cardinal

numbers || numerals

– I assume that he knows them by heart – up to

the word “five” and with each numeral he takes an

apple from the box that

has the colour of the square || that has the colour of the square

from the drawer. – This is

how one works || In this way & in similar

ways one operates with words. –

“But how does he know where and how he is to look up

the word ‘red’ and what he has to do with the

word ‘five’?” – Well, I

am assuming that he acts, as I

have described. The

explanations || Explanations come to an end

somewhere. – What is || What's || But

what's the meaning of the word

“five”? – There was no

question of any || such an entity

‘meaning’ here; only of the way in

which “five” is used. || Nothing of that sort was being discussed,

only the way in which “five” is

used. |

That philosophical concept of

meaning is at home in a primitive notion

of || way of describing

◇◇◇ || picture of the

way in which our language functions. But

one || we might

also say that it is the

notion || a picture of a more primitive

language than ours. |

Let us

imagine a language for which the description which

Augustine has

given would be correct. The language

shall help a builder A to make himself understood by

an || is to be the means of communication between a builder

A and his assistant B.

2 ¤ A is constructing a building out of building

stones || blocks; there

is a supply of || are cubes,

columns, slabs and beams. B has to hand him the

building stones in the order in which

A needs them. For this purpose they use a

language consisting of the words:

“cube”, “column”,

“slab”, “beam”. A

shouts || calls out the words;

– B brings the stone that he has learned to bring at this

call.

Take || Regard this as a complete primitive language. |

Augustine

describes, we might say, a system of communication;

only not

everything || not everything, however, that we call

language is this system. (And this must be said || one must say in ever so many cases where || when the question arises, || : “can this description be used or can't it be used? || is this an appropriate description or not?”. The answer is, “Yes, it can be used || is appropriate; but only for this narrowly restricted field, not for everything that you were professing || professed to describe by it.” Think of the theories of the economists.) |

It is as though

someone explained: “Playing a game consists in

moving things about on a surface according to certain

rules …”, and we were to

answer || answered him: You

are apparently || seem to be

thinking of games played on a board; but

those || these

aren't all the games there are.

You can put your description right by confining it

explicitly to those games. |

Imagine a

way of

writing || type || script in

which ◇◇◇ letters

are used to indicate || stand

for sounds, but are used also to

indicate emphasis || as accents and as

marks of punctuation || punctuation

signs. (One can regard a

way of

writing || type || script as a

language for the description of sounds.) Now suppose

someone understood || interpreted

this || our

way of

writing || type || script

as though it were one in which to every letter

there simply corresponded a sound || all letters just stood for

sounds, and as though the letters here did not

have other very different

functions as well || also have quite different

functions. – An oversimplified view of the type

like this one resembles, I believe, || Such an oversimplified

view of our script is the analogon, I believe, to

Augustine's

view of language. |

If one considers example (2)

one || we look at our example (2) we may perhaps

begin to suspect || get an idea

of how far the commonly

accepted || general concept of the meaning of

words || a

word surrounds the

functioning || working of

language with a mist that makes Primitive forms of language of this sort are what the child uses when it learns to speak. And here teaching the language does not consist in explaining but in training. |

We

might || could imagine that the

language (4) is the

entire language of A and B; even the entire

language of a tribe. The children are brought up to carry

out just these || these

activities, to use just these || these

words and to react in just

this || this || the activities in

question, to use such & such words and to react in such

& such a way to the words of

another || others.

An important part of the training will consist in the teacher's pointing to the objects, directing the attention of the child || child's attention to them and at the same time pronouncing a word; for instance, the word ‘slab’ in pointing to this block. (I do not || don't want to call this “ostensive explanation” or “definition”, because the child can't as yet ask what the thing is called. I will call it “ostensive teaching of words”. – I say it || this will constitute an important part of the training, because that || this is the case among || so with human beings, not because it couldn't be imagined || we couldn't imagine it differently || otherwise.) This ostensive teaching of the words, one might say, fixes || makes an associative connection between the word and the thing. But what does that mean? Well, it may mean various things; but probably what first comes to one's mind is that || occurs to one is that || what first occurs to one is probably that an image of the thing comes before the child's mind when it hears the word. But suppose that happens – is that the purpose 4 ¤

of the word? –

Yes,

it || It may be

the || its

purpose || aim. – I can imagine

words

(i.e. here || I

mean || i.e. series of sounds)

having an application of this sort. || such a use of words

(i.e. series of

sounds). (Their utterance is so to speak

the striking of || To pronounce them would be like

striking a key on

the || a piano of

ideas || images.)

But in the || our language

(3 || 4) it is not

the purpose || aim of the words

to call up

ideas || images.

(Though it may of course turn out

that this is conducive || this may, of course, be found to be

helpful to their real

aim || purpose.) But if that is what the ostensive teaching brings about, – shall I say that it brings about the understanding of the word? Doesn't someone || he understand the cry || order “slab!” if he acts in such and such a way on hearing it? – The ostensive teaching helped to produce this no doubt || indeed helped to bring this about, but only in connection with a certain course of instruction || training. With a different course of instruction || training the same ostensive teaching of these words would have brought about quite a different understanding. – Of that || this more later. || at a later point. “When I connect || By connecting up the rod with the lever || this lever with this rod by means of the || a peg, I make the brake ready for use || put the brake in order.” – Yes, given all the rest of the mechanism. Only together with this mechanism is it a brake lever; and without || detached from its support it isn't even a lever, but can be all sorts of things, or nothing || it may be anything. |

As the language (3) is used in

practice || In the use of the language (4)

the one party calls out the words and the other acts according to

them. But in the

teaching || instruction of the language || In the

teaching of this language however there

will be || you will find this

procedure: the one who is learning || pupil calls the objects || blocks by name || their names; that

is, he speaks || pronounces

the word when the teacher points to the

stone || block. –

In fact you || we will find

here even

the || an even simpler exercise: the pupil repeats

the words that || which the

teacher recites to him || pronounces for

him: both

processes || of these

exercises that resemble

language. || already primitive uses of

language. 5 ¤

We may even imagine that the entire process of the use of the words || use of the words we make in (4) is one of those games by means of which children learn our || our children learn language. I will call these “language games”, and I will frequently speak of a primitive language as a language game. And one might call the processes || exercises of calling the stones || blocks by their names and of repeating the word that has been spoken out || words which the teacher has pronounced language games as well. Think of the various || various uses that are || the use made of words in nursery-rhymes. |

Let us

now consider an extension of the language

(4): Besides the

four words “cube”, “column”

etc., let it contain a series of words

applied in the

way in which the grocer in (2)

applies || applied

the numerals, – it

can || may be the

series of the

letters of the alphabet; further, let there be two

words, which we may

pronounce || say || let us

choose “there” and

“this”, since this already suggests

roughly their purpose, – they are

to be used in connection with a pointing

movement of the

hand || gesture; and finally let us use

certain little squares || bits

of paper of various colours. A now

gives a command of the || this sort:

“d slab there” – at the same

time letting the assistant

see || showing his assistant a coloured square, and

with the word “there” pointing to a

certain place. B takes from the supply

of slabs one || a

slab of the same colour as the coloured square for each letter of the

alphabet up to “d” || for each letter of

the alphabet up to “d” a slab of the same

colour as the coloured square and brings it to the place

which A indicates. – On other occasions A

gives the command “this there” – with

“this” he points

to || at a building

stone || block – and so

on. |

When the child learns this

language it has to learn the series of

“ || “numerals” || ”

“a”, “b”,

“c”, … by heart. – And it

has to learn their use. Will an ostensive teaching of

words come || enter into

this 6 ¤ instruction

also? – Well,

someone || one

will point at slabs, for instance, and count: “a,

b, c slabs”. A greater similarity

with the ostensive teaching in example (3) would appear in the

ostensive teaching of numerals when || There would be a

greater similarity between the ostensive teaching in (4) and the

ostensive teaching of numerals if these are not used for

counting but rather to indicate || refer

to groups of objects that can be grasped

with || by the eye.

This is the || In this

way children learn the use of the first five or six

cardinal

numbers || numerals. Are

“there” and “this”

taught || Do we teach “there” and

“this” ostensively? –

Think of || Imagine

how you || one might teach their

use. You point to places and things; –

but here || in this case the

pointing occurs in the use of the words

as well || also,

and not simply in the

learning || teaching of

it || the use. –

|

What || Now

what do the words of this language denote? – How can

this show itself – what they denote –

except || What they denote – how is this to appear,

unless in the way they are used? And this

is what we have described. The expression, “this

word denotes that || so

& so” would have then to

be || now become a part of this

description. Or: the description

should || is to be put in the

form: “The word … denotes

…”. Now one can certainly shorten || it certainly is possible to condense the description of the use of the word “slab” in this way, and say || into saying that this word denotes this object. That || This is what one would do, for instance, if the question was || were simply || if the question were, for instance, to prevent the misunderstanding of thinking that the word “slab” referred to the kind of building stone that || block which we actually call a “cube”, while || and the particular sort of “reference”this is || , however, i.e. everything else about the use of || all the rest of the game with these words, is || were familiar. Similarly one might say that the signs “a”, “b”, “c”, etc. denote numberswhen this removes || , if this is to remove the misunderstanding of thinking that “a”, “b”, “c”, play the role in the || our language which actually is 7 ¤ played by

“cube”, “column”,

“slab”. And one can say also that

“c” denotes this number and not that, –

when this is to explain, say, that the letters are to be used in

the order “a”, “b”,

“c”, “d”

etc., and not “a”,

“b”, “d”,

“c”. But because you assimilate || by assimilating in this way the description || descriptions of the use of these words to one another, their use doesn't || uses of words to one another, their uses don't grow || become more similar: || . For, as we have seen, their use is || uses are of widely different sorts. |

Think of the tools in a tool

chest: There is || It has a hammer,

a pair of pincers, a saw, a screw-driver, a ruler, a

pot of glue, glue, nails and screws. –

Different as the functions of these

objects are, just as different || As different as the

functions of these objects are the functions of

words. (And there are similarities in the one case

and in the other.) |

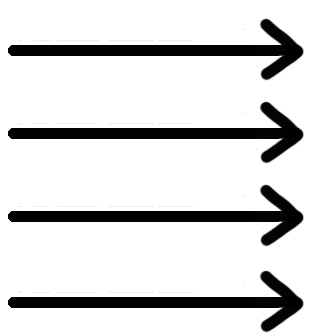

What confuses us, of

course, is the uniformity of their appearance when

the words are spoken to us or when we meet

them in writing || we hear the words or see them written

or in print. For their

application || use isn't so clearly there

in front of us || before our

eyes. Especially not

if || when we are

philosophizing || doing

philosophy. |

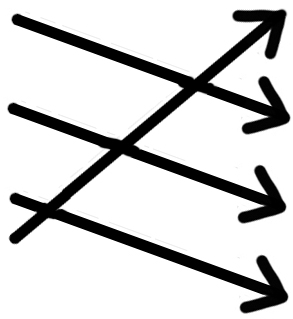

It is like when

we look || looking || As when we look

into the driver's cabin of a locomotive: we see

handles that || which all look

more or less alike.

(That is

understandable || That's natural, since

they are all supposed || made

to be grasped || held with

the hand.) One || But one is the crank that can be moved continuously over

(it regulates the opening of an air valve) || valve that can

be regulated by continuous degrees; the other || another

is the handle of a switch, which has only two

positions in which it is

effective || effective positions, it's either shut or

open; a third is the handle of a brake lever,

the more strongly || harder

you pull it the more strongly the brake is applied; a

fourth, the handle of a pump, works only as long as it is

8 ¤ moved back

and forth. |

If we say: “every word of

the language denotes something”, –

then, so far, nothing at all has

been said || we've said nothing at

all; || , that is, unless we

explain precisely what distinction we

wish to make. (It might be that we

wanted || wished to

distinguish the words of our language

(9 || 11) from

“nonsense” words such

as || words ‘without meaning’ which

occur in Lewis

Carroll's

poems.) |

Suppose someone

said, || :

“All tools serve to modify something.

Thus the hammer modifies the position of the nail, the

saw the form || shape of the board,

etc..” – And

what is modified by the ruler, the glue pot, the

nails? || And

what does || what's

the ruler modify, or the glue pot, or the

nails? – “Our knowledge of the

length of the || a

thing, the temperature of the glue and the firmness of the

chest || box.”

– Would anything be gained by this

assimilation under one expression || of our expressions? – |

The

word

“denote || name” || The expression “the name of an

object” is probably

best || very straightforwardly applied where

the sign || mark || name is actually a

mark on the object which it

denotes || itself.

Suppose then that there are signs || marks scratched on the tools which A uses in building. When || If A shows his assistant a sign || character of this sort, then the assistant brings the tool which bears that sign. || mark, character. In this and in more or less similar ways a name denotes a thing, and a name is given to a thing. (Of this more later.) – It will often prove useful if we say to ourselves in doing philosophy || in doing philosophy we say to ourselves: Naming something, that is something like hanging a name plate on || attaching a label to a thing. – |

What about the

colour-samples that A shows to B, – do they

belong to the language? As you like. They

don't belong to the verbal || our spoken language; but if I say to someone,

“Pronounce 9 the word

‘that || the‘”,

you will count the

second “the” also as || call the second

“the” also a part of

the sentence. Yet it plays a very similar role to that of

a coloured square || bit of

paper in the language game

(11): it is a sample

of what the other person is supposed to say, just as the

coloured square is a sample of what B is supposed to

bring. It is the most natural thing and it causes the least confusion if we reckon || count the samples among the instruments of the language. |

We may say that in language (11) we have

various parts of speech. For the functions of

“slab” and “cube” are more alike

than the functions of “slab” and

“d”. But

how || the way we

classify the words together as various

parts of speech will depend on the purpose of the classification,

and on our inclination. Think of the different points of view from || according to which one might classify tools as different kinds of tools. Or chess pieces as different kinds of pieces. |

Don't

let it bother you that the languages (4)

and (11) consist only of

commands. If you are inclined to say that they are

therefore incomplete, then ask yourself whether our

language is complete; whether it was complete before the symbolism

of chemistry and the infinitesimal calculus were

embodied in it: for these are, so to

speak || as it were, suburbs of our

language. (And with how many houses or streets does a

city || town begin to be a

city || town?)

One || We can

regard our language as an

old || ancient

city || town, a

quarter || the center a maze of narrow

alleys and squares, old and new houses, & houses

with additions from various periods; and all this surrounded by a

mass of new suburbs with straight and regular streets and uniform

houses. 10 ¤

One can easily imagine a language which consisted || consists only of commands and announcements || dispatches || reports in battle. – Or a language which consisted || consists only of questions and an expression of affirmation and of denial. And || – and countless others || other things. – And to imagine a language means to imagine a way of living. |

But let's see: is the

cry || call

“slab!” in example

(4) a sentence or a word? – If it's a word, then

surely it hasn't anyway the same

meaning as the word that's pronounced the

same || “slab” in our

ordinary language, for in our language

(4) it is a

cry || call; but if

it's a sentence, then surely it isn't

the elliptical sentence “slab!” of

our language. ‒ ‒ ‒ As regards the first

question, || : you can

call “slab!” a word, and you can

also call it a sentence; perhaps

fittingly || best a

“degenerate sentence” (as one

speaks of a degenerate hyperbola). And it is precisely

our “elliptical” sentence. ‒ ‒ ‒ But

that is surely just a

shortened form of the sentence, “Bring me a

slab”, and || isn't this a shortened form of the

sentence “Bring me a slab”?

And there isn't any such || such

a sentence in

example || the language

(4). – But

why should I not || shouldn't

I rather call the sentence

“Bring me a slab” a lengthening of

the sentence “slab!”?

‒ ‒ ‒ Because the person who calls out

“slab!” really means “Bring me

a slab!”. ‒ ‒ ‒ But how do you do

that || this,

meaning this while you say

“slab”? Do you say the unshortened

sentence to yourself? And why should I, in order to

say what you mean by the cry || call “slab!”, translate

this expression into another? And if they mean the

same, – why shouldn't I say:

“When you say ‘slab!’ you mean

‘slab!’”? –

Or: Why shouldn't it be possible

for you to mean “slab!”, if you can mean

“Bring me the slab”? ‒ ‒ ‒

But when I shout “slab!”, then surely what

I want is 11 ¤ that he

shall || shall bring me a

slab. ‒ ‒ ‒ Certainly, but does

“wanting this” consist in the fact that

you, in some way, think || think in

any form a different sentence from the one you

speak? – |

“Well

but || But if someone says ‘Bring

me a slab’ it looks now || now looks as

though he could mean this expression as one long word, –

correspondingnamely || , that

is, to the word || one word

‘slab!’.” – Can one

mean it sometimes as one word and sometimes as four

words? And how does one generally mean it? – I

believe || think that what we

shall be inclined to say: is that we mean the sentence

as a sentence of four words when we are using it as

contrasted with sentences such

as || like, “Hand me

a slab”, “Bring him a

slab”, “Bring two slabs”,

etc.: as contrasted, that is, with

sentences which contain the words of our command in

different || other

combinations. – But what does using one sentence

as contrasted with || in

contrast to other sentences consist

in? Does one have these other sentences in

mind at the time? And all of them?

And while one is speaking the sentence, or before or

afterwards? – No. Even if such an

explanation has some attraction for us, we have only to

think || consider

for a moment what actually happens in order to see

that we are on the wrong road here || a

wrong track. We say we use

that || this

command as contrasted with || in contrast

to other sentences. because

our language contains the possibility of these other

sentences. || because in our language

these other sentences are possible. Someone who

did not understand our language, a foreigner who had

frequently heard someone giving the command “Bring

me the slab”, might suppose that this entire series of

sounds was one word and corresponded, say, to the word

“building

stone || block”

in his language. If he had then to give this command

himself, he would perhaps pronounce it

differently and we 12 ¤ should say:

He pronounces it so

curiously || queerly because he

takes it to be || thinks it is

one word. – But then doesn't

anything || something different

happen in him when he utters

this sentence || it, corresponding

to the fact that he takes the sentences to be || views the

sentences as || regards the sentence as one

word? The same thing may happen in him, or again

something different may. What happens in you

when you give a command of that sort? Are

you conscious that it consists of four words while you

are uttering it? Of course, you have a

mastery of || know this language,

in which there are those other sentences also,

– but is this

mastery || knowing something

that happens while you are uttering the

sentence? – And I have admitted,

that the foreigner will

probably give the sentence he views differently a

different pronunciation; || who views

the sentence differently will probably also pronounce it

differently, but what we call

the || his wrong

view || idea doesn't

have to

lie || necessarily consist in

anything that accompanies the uttering of the command.

(Of

that || this

more later.) |

The sentence is

not ‘elliptical’ because it

leaves out || omits

something which || that we

mean || think when we utter it,

but because it is

shortened || abbreviated,

in

comparison || as compared with a

particular standard of our grammar. – One might

here make the objection:

“You admit that the

shortened || abbreviated and

the

unshortened || unabbreviated

sentence have the same meaning. –

What || Well,

what meaning have they

then? || ?

Is there

not || Isn't there one

verbal || an expression for

this meaning?” – But doesn't

the || their identical meaning

of the sentences consist in their having the same

application || use?

(In Russian they say “stone

red” instead of “the stone is

red”; is the copula left out of the meaning

for them || don't they get the full meaning, as

they leave out the copula? or do they

think the

copula || it to themselves without

pronouncing it? –) |

One can

easily imagine a language also || also

imagine a language in which B, in reply to a

question by A, informs him of || has

to report to him the number of slabs or

cubes 13 ¤

|| stacked up in some place; or

the colours and forms || or

shapes of

the || certain

building-stones that lie in one

place and

another. || building-blocks.

The purport of such a report might then be: “five slabs.”. ¤ || Such a report might then say || be of the form: “five slabs.”. Now what is the difference between the report, or assertion, “five slabs.”, and the command “five slabs!”? – Well, || It is the role which the utterance of || saying these words plays in the || our language game || games. But the tone of voice in which they are uttered will probably || probably the tone of voice in which they are uttered will be different as well || too, and the facial expression and various other things. But we can also imagine || it may well be that the tone of voice is the same in both cases – for a command and a report can || may be uttered in various || a lot of different tones of voice and with various || a lot of different facial expressions – and that the difference lies in the application alone || may lie only in what is done with the words “five slabs”. – (Of course we might also use the words “assertion” and “command” just to indicate a grammatical combination || form of a sentence or || and a word || particular intonation, just as one calls || would call the sentence, “Isn't it glorious weather today?”, a question, even though || although it is used like || as an assertion.) We could imagine a language in which all assertions had the form and the intonation of a rhetorical question; or every command || in which every command had the form: “Would you like to do that || …?”. One would then || might perhaps say in this case: “What he says has the form of a question but it is really a command”, i.e. has the function of a command in the practical employment of language. || . (Similarly one says “you will do that || so & so” not as a prophecy but as a command. What makes || would make it the oneand || , what the other?) |

Frege's view that in an

assertion there is contained || an assertion contains

a

supposal || an Annahme,

and that it is this

that || which is asserted, is

based really || really

based on the possibility that there is in our

language of writing every 14 ¤ assertion

sentence in the form: “It is asserted

that so and so is the case”. But “that

so and so is the case” is not a sentence in our language

– it || this

is not yet a move in our language game.

And if I

write instead of “It is asserted that

…”, || instead of “It is asserted

that …”, I write “It is

asserted: so and so is the case”, then in this

case the words “It is asserted” are

quite superfluous. We might very well write every assertion in the form of a question followed by an affirmative reply; thus instead of “It's || It is raining”, “Is it raining? Yes.”. Would that show that in every assertion there is || every assertion contained a question? |

Of course one

has a right to use a mark of assertion || an assertion

sign in contrast, for instance, to a question

mark. The mistake is only in thinking || to

think that the assertion now consists

in || of two acts, the

consideration and the

assertion || considering and the asserting (assigning

the truth value, or something of that

sort || whatever you call it), and that we

perform these acts according to the signs

in || of the sentence,

rather || almost as we sing

from notes. We

might certainly compare reading loudly or

softly || silently according to the written

sentence with singing from notes, || What can be compared

with || to the singing from notes is the reading aloud,

or to oneself, of the signs of the sentence; but not

“the meaning”

(◇the thinking) of the

sentence that is read. |

The important

sense of || point

about || of

Frege's

mark of

assertion || assertion sign is put

perhaps || perhaps put best if

we say: || by saying: it indicates clearly

the beginning of the sentence. –

That || This

is important:

because || for our

philosophical difficulties concerning the nature of

“ || ‘negation” || ’

and of

“ || ‘thinking” || ’,

originate || spring in a sense

from || in a sense, are due to the fact that we

don't

see || realise that

a sentence || an

assertion “⊢

not p”, or

“⊢ I believe

p”, and the

sentence || assertion

“⊢

p” have

“p” in common, but not

“⊢

p”. (For if I hear someone

say, || the words

“it's raining”, then I don't

know what he has said if I don't know 15 |

¤ whether I have heard the

beginning of the sentence.) |

How many kinds of sentence are there,

though || But how many kinds of sentence are

there? Assertion, question and command

perhaps || Is it assertions, questions and

commands? – There are

innumerable kinds: innumerable different

kinds of

application || applications

of everything || all that we

call “signs”, “words”,

“sentences”. And this variety is

nothing that is fixed, given once and for

all, but new types of language, new language games

– as we may say – spring

up || come into being and others

grew || become obsolete and

are forgotten. (We can get a rough picture

of this from || A rough picture of this we can get

if we look at the

changes || transformation

in || which happen in

mathematics.)

The expression “language game” is supposed to emphasise here || used here to emphasise that the speaking of the language is part of an activity, or || part of a way of living. || of human beings. Bring the variety of the language games before your mind by || To get an idea of the enormous variety of language games consider these and other examples || examples, & others: commands || commanding || giving commands, and acting according to commands; describing an object according to its appearance, or according to || giving a description of an object by describing what it looks like, or by giving its measurements; producing an object according to a description (drawing); reporting a course of events || an event; setting up || making a hypothesis and testing it; presentation of || presenting the results of an experiment in tables and diagrams; performing in a theatre || acting a play; singing a catch; guessing riddles || asking riddles and guessing them; 16

making a joke, or telling one; solving an example || a problem in applied arithmetic; translating from one language into another; entreating || requesting, thanking, swearing, greeting, praying. – It is interesting to compare the variety of the instruments of our language and of their applications || the ways they are applied || their various uses – the variety of the parts of speech and of the kinds of || kinds of words & of sentences – with what logicians have said about the structure of our language. (And the author of the Tractatus Logico-philosophicus as well || Including the author of Tract. Log.-phil.¤) |

If we don't see that there is a multitude of

language games, we are inclined to ask: “What

is a question?” Is it the statement that I

don't know so and so, or is it the statement

that I wish the other person would tell me …?

Or is it the description of my mental state of

uncertainty? – And is the cry

“help!” a description of that

sort || a description? || such a

description? Think of what widely different things we call “description” || descriptions”: the description of the position of a body by means of its coordinates: the description of the course of || changes in a sensation of pain. One can of course put instead of the usual form of the question || Of course one can replace the usual form of a question by that of the || a statement or a description: such as “I want to know whether …”, or “I am in doubt as to whether …” – but one hasn't thereby brought the different language games any nearer to one another. The significance of such possibilities || this possibility of transforming, for instance, all declarative sentences || assertions into sentences that begin 17 ¤ with the

clause || words “I

think” or “I believe”

(i.e. so to speak into descriptions of my

inner life || mental states)

will appear later. |

It is sometimes said || said

sometimes: animals don't speak, because

they

haven't || lack the

necessary intellectual capacities. And this

means: ‘they don't think, therefore they

don't speak’. But the fact is

that they just don't speak.

Or better || rather: they don't use

language. (If we

disregard || except

the most primitive forms of language.)

Commanding || Giving

orders, asking questions,

recounting || describing,

prattling, belong to our natural history just as walking,

eating, drinking, playing do. (It makes no difference

here whether the speaking is done with the

mouth or done with the hand.)

|

This is connected with the view that

the || fact that we think that the learning of

the language consists in naming objects;

namely || viz.

human beings,

forms || shapes, colours,

pains || aches, moods,

numbers, etc..– As we

have said, – naming is something like

affixing a nameplate

to || putting || fastening

a label to a thing. One may call

this || And this one might call

the || a preparation for the use of a

word. But for what is it a

preparation? |

“We name things and can now || now we can

talk about them. We

can || ; refer to them in what we

say.” – As though with the act

of naming we had already at hand what we go on to do

afterwards || all that happens after it were already

fixed. As though there were only one thing

that is called “speaking about

things”. Whereas actually we || we actually do

things of the most widely different

kinds || the most widely different kinds of things with

our sentences. Think only of the

interjections. –

With || – with their

entirely || utterly || very

different functions.

Water! Away! || Get out! Ouch! Help! 18

Beautiful! || Lovely! No! Are you still inclined to call these words “giving names to || “names of objects”? |

In

the languages (4) and

(11) there was no such thing as asking

what

something || a

thing is called. This and its correlate, the

ostensive explanation, definition, is, we might say, a separate

language game. That means really: we are

brought up || taught, trained,

to ask “What is

that || this

called?”, – and then the

naming follows || name is

given. There || And

there is also a language gameof || : inventing a name for

something. That is, of

saying || I.e., to

say, “That's || This

is called …” and then

using || to use the new

name. (In this way, for

instance || e.g.,

children name their dolls and then go on to talk

about them. In this connection consider at

the same time a very special use || what a very

special use we make of a personal name: it is

when we use it to call someone.) || … how special that

use of a personal name is with which we call the person

named.) Now you can give an ostensive definition of || we can ostensively define a personal name, a colour word, a || the name of a material, a numeral, the name of a direction || the name of a point of the compass, etc., etc.. The definition of two: “That || This is called ‘two’” – pointing to two nuts – is perfectly exact. – But how can you define “two” in that || this way? The person to whom you are giving || give the definition doesn't || won't know then || then know what it is you want || wish to call “two”; he'll suppose that you are calling || have called this group of nuts “two”. – He may suppose this, – but perhaps he won't suppose it. || . He might also do just the opposite: when I want to assign a name to this group of nuts he might take this for || to be the name 19 ¤ of a

number. And equally, if I give an ostensive definition

of a personal name, he might take

this || it to be the name of a

colour, the name of a race, even the name of a

direction || point of the

compass. That is, the ostensive

definition can in every case || all

cases be interpreted in one way and also in others. || this way or in that way. |

You may

say: “Two” can

be defined ostensively only in this

way: “This number is called

‘two’”, for || .

For the word “number”

shows here || here

shows in what place in the language

– in the grammar – we

set || put || what place in our

language – in our grammar – we assign to the

word; but this means that the word “number” must

be explained before that ostensive definition can be

understood. – The word “number” in

the definition does

certainly || indeed indicate

this place, – the post to which we assign || which we

assign to the word. And we can prevent

misunderstandings in this way, by saying,

“This colour is called so and so”,

“This length is called so and

so”, etc.. That

is: misunderstandings are often avoided in this

way. But can the word “colour”,

then, or “length”, be

understood only in this way? –

Well, we'll || we

shall have to explain them. – Explain them by of other words, that

is || That is, explain them by means of other

words! And what about the last explanation

in this chain? (Don't say:

“There isn't any ‘last’

explanation”;

that || . This is exactly as though you

were

to say || said, “There

isn't any last house in this street: you can

always build another one

further”.) || .”)

Whether the word “number” in the ostensive definition of two is necessary || is necessary in the ostensive definition of “two” depends on || upon whether he understands this word differently from the way I wish him to || takes this word in a different sense from the one I wish || misunderstands my definition if I leave out the word. And that || this will depend on the circumstances under which the definition is given and on the person to whom I give it. 20 ¤

And how he “understands” the explanation appears in how || will appear in the way he makes use of the word explained. |

One might say then:

The ostensive definition explains the use – the

meaning – of the word if it is already clear in

general what kind of role the word is to play in

the language. Thus if I know that someone wants to

explain a colour word to me, then the explanation

“That's || This

is called ‘sepia’” will

help me to get

an understanding of || make me understand the

word. – And you can say this if you

don't forget || as long as you

remember that there are all sorts of questions connected

with || all sorts of questions now attach to the

word || words

“to know”

or || and “be

clear”. You have to know something already in order to be able to || before you can ask what it || something is called. But what do you have to know? If you show someone the king in a chess game || set of chess men and say, “That || This is the king of chess”, you do not thereby explain to him the use of this piece, – unless he already knows the rules of the game except for this last point: the form || shape of the king-piece. || king. We can imagine that he has learned the rules of the game without ever having been shown a real chessman. The form || shape of the || a chessman corresponds here to the sound or the shape of a word. But we can also imagine someone's having learned the game without ever having learned or formulated rules. He has perhaps first learned very simple games on boards by watching them and has proceeded to more and more complicated ones. To him also you might give the explanation, “That || This is the king”, if, for instance, you are showing him chess pieces || men of an unusual form || shape. And this explanation teaches him the use of the figure || piece only because, as we 21 ¤

might say, the place in which it was put was already

prepared. || we had in the game already prepared the

place in which it was to be put.

Or again: We shall say the explanation

teaches him the use, only when the place

is already || has already

been prepared. And it is so

here || prepared in this case not

because the person to whom we are giving the

explanation already knows rules, but because he has

already mastered the game in a different

sense. || in a different sense, already mastered a

game. Consider still another case: I explain the game of chess to someone and begin by showing him a pieceand || , saying, “That || This is the king. – He || It can move in this and this way, etc. etc.”. – In this case we shall say: the words “That || This is the king” (or, “That || This is called ‘king’”) are an explanation || explain the use of the word || words “the king”, only if the person learning || we teach already “knows what a piece in a game is”: when he has already played other games, say, or “has watched the play with understanding” || watched ‘with understanding’ games played by other people, and so forth || the like. And only then will he be able || in a position to ask relevantly, in learning the game, “What's that || this called?” – namely || that is, this piece. We may say: it is sensible for someone to ask what the name is only || there is only sense in someone's asking for the name if he knows already || already knows what to do with it. || the name. We || For we can imagine also that the person who is asked answers, “decide on the name yourself”, – and then the person who || whoever asked the question would have to make himself responsible for everything || catch on to everything himself || ¤ I have asked, answers, “give it the || a name yourself”, – and then I should have to provide everything myself. |

Anyone who comes

into a foreign land || country

has frequently || will often

have to learn the language of the

inhabitants there

through || by ostensive

definitions || explanations which

they || people give him; and he

has frequently || will often

have to guess the interpretation of these

explanations, & will guess it

often || sometimes correctly,

often || sometimes

wrongly. And now we can say, I think: 22 ¤ Augustine describes the || the

child's learning of

human || of language || to

speak as though the child

came || had come to a foreign

country and did not

understand || without understanding the

country's || its

language; that is, as though the child already had a

language, only not this one. Or, as though the child

could already think but could not

speak yet || yet

speak. And here “think”

means || would mean

something like: speak to

oneself || himself.

|

But what if someone

objected, || :

“It

is

not || isn't true that someone must have mastered a

language game already in order to understand an ostensive definition,

but he has only – obviously – || only

he's || you must already have mastered a language

game in order to understand an ostensive definition, but of course,

you've got to know (or

guess) what the person

explaining || man who gives the explanation

is pointing to. Whether, for

instance, || : e.g.,

whether to the

form || shape of

an || the object, or to its

colour, or to the number of the

objects, etc.,

etc..” – And what does

“pointing to the

form || shape”,

“pointing to the colour” etc.

consist in, then? Point to a piece of

paper. – And now point to its

form || shape, –

now to its colour, – now to its number

(that sounds queer). – Well, how did you do

it? – You will say you “meant”

something different each time you pointed || each time you pointed

you “meant” something

different. And if I ask

how that takes

place || you how that takes place || this is

done || how you do this, you will say you

directed || concentrated || concentrate

your attention on the colour, on the

form || shape

etc.. But

then || now I ask again how

that || this

takes place. || is

done. Suppose someone points to a vase and says, “Look at that || this glorious || gorgeous || marvellous blue! – the shape doesn't matter.” – Or, “Look at that || this magnificent || wonderful shape! – the colour is || colour's unimportant.” – Undoubtedly you will do different things || something different in each case if you comply with both these requests || do what he asks you. But do you always do the same thing when you direct your attention to the colour? Imagine various cases – I will suggest some: || e.g. these: – “Is this blue the same as that? Do you see a 23 ¤

difference?” – You are mixing colours || paints on a palette and you say, “This blue of the sky is hard to find || get.” “It's going to be fine, you can see the blue sky already again.” “Look what different effects these two blues give.” “Do you see the || that blue book over there? Please bring || fetch it.” “This blue signal light means …” “What is || What's this blue called? – is it “indigo”–?” Directing the attention to the colour sometimes means shutting out the outlines of the || a shape with one's || your hand, or, not directing one's gaze || looking directly at the contour of the thing; sometimes it means staring at the thing and trying to remember where one has seen this colour before. You direct your attention to the shape of a thing, sometimes by sketching || drawing it, sometimes by squinting || half closing the eyes || screwing up the eyes so as not to see the colour clearly, etc., etc.. I want || wish to say that: this and things like it happen || is the sort of thing that happens while one “directs the || one's || you ‘direct your attention to this and that” || something’. But that || this is not the only thing that allows us to || it isn't just this which makes us say, || that someone is directing his attention to the shape, to the colour, etc.. Just as “making a move in chess” does not || doesn't only consist in the fact that a piece is pushed across the board in such and such a way || pushing a piece from here to there – but also not || nor in the thoughts and feelings that accompany the move in the person making it – but rather in the circumstances that we call “taking part in || playing a chess game || game of chess”, or “solving a chess problem”, and so forth || the like. |

But suppose someone

says || said, || :

“I always do the same thing when I direct my attention to

the || a shape: I

follow the

contour || outline with my

24 ¤ eyes

and feel || with the

feeling

… || …”. And suppose

this person gives to someone else the ostensive

definition || explanation,

“That || This

is called a

‘circle’”, by pointing¤

with

all these experiences, to a circular object || to a circular object

& having all these

experiences: –

can't || . Can't the

other person still interpret this explanation

differently, even

though || although he sees that the person giving

the explanation || it follows

the shape with his eyesand || , even

though || if he feels what the

person giving the explanation feels? That

is || is to say, this

“interpretation” can

also || may consist in the way in which

he makes use of || uses || use he now makes

of the word, for

instance || e.g.

what he

points to when he is || in his pointing to such & such an

object when given the

command, || :

“Point to a circle”. – For

neither the expression, “meaning the explanation in such and

such a way”, nor the expression, “interpreting

the explanation in such and such a way”, indicates a

definite || particular process

which

accompanies || accompanying the giving and

hearing || receiving of the

explanation. |

There are

certainly || indeed what

one

can || we may call || might be called

“characteristic experiences”

for || of

pointing to the shape (for

instance) || (e.g.) to the

shape || to a shape,

e.g.¤

For

example || instance, tracing the contour with

one's finger || Tracing the outline with

one's finger, for instance, or with

one's

gaze || eyes, in

pointing. – But little

as this happens in all cases in which I “mean the

shape”, – equally little is it true that any other any

other characteristic process occurs || just as this

doesn't happen in all cases in which I ‘mean the

shape’, – similarly there isn't any

other characteristic process either occuring || no other

characteristic process occurs in all these

cases. But

also, || even if

something of the sort || such

process did

recur || occur

in all of them, it would still depend

on || upon the

circumstances – i.e.

on || upon what

happened before and after the pointing –

whether we

should || would

say, || :

“He pointed to the shape and not to

the colour”. For the words || expressions “pointing to the shape”, “meaning the shape” etc. are not used like these || as these || these others are || like these:– “pointing to the book”, “pointing to the letter ‘B’ and not to the letter ‘u’” etc.. – For think only of || Just think how differently we learn the use of the words || expressions: “pointing to 25 |

¤ this thing”, “pointing to that

thing”, and on the other hand “pointing to the

colour and not to the shape”, “meaning the

colour”, etc.,

etc.. As I say || As I have said, in certain cases, particularly in pointing ‘to the shape’, or ‘to the number’, there are characteristic experiences and ways of pointing, – “characteristic” because they frequently, not always, || (not always) recur || occur where shape or number is “meant”. But do you also know a characteristic experience for pointing to a figure || piece in a game as piece in a game || chessman as a chessman? – And yet one || you may say, || : “I mean this piece in the game || chessman is called ‘king’, not this particular piece || block of wood that I'm pointing to.” And we do here, what we do in 1000 || a host of similar cases: Because || as we can't || aren't able to mention || point out some one bodily action that || which we call “pointing to the shape” (as opposed, e.g., to the colour) we say that a mental activity corresponds to these words. Where our language leads us to expect a body || look for a physical thing, and there isn't any || a body || thing, there, || ; there we are inclined to say, is a mind. || put a spirit. |

“What is the relation between

names and what they name || the

named?” –

Well, what is it? Look at

the || our

language game (4), or

at some other language game; you can see there || that's

where you'll see what this relation consists

in. This relation may,

among various other things, || Among various things, this

relation may consist also in the fact that

hearing the name calls up an image of the thing

named in our minds || in our minds an image of the

thing¤, and it

sometimes consists among other things also in

the fact that the name is written on the thing named, or that

it || the name is

uttered when the thing named is

pointed to. But what does the word “this” name || is the word “this” a name of in the language game (11), or 26 ¤ the word

“that” in the ostensive explanation

“that || in the ostensive explanation

“this is called …”?

Well, if you don't want to

introduce || give rise

to || produce confusion it is best

not to say that these words name anything.

– And, curiously

enough, it was once said of the word

“this” that it is the real name.

Everything else that we call

“name” is so || being a

name only in an inexact, approximate

sense. This curious view has its origin in a tendency to sublimate – as we might call it – the logic of our language. The proper answer to it is: We || we call widely different things “names”; the word “name” characterises many different sorts || kinds of use of a word || uses of words, related to one another || each other in many different ways; – but among these kinds of use || uses is not that of the word “this”. It is true that we often, for instance || e.g. in giving an ostensive definition, point to the || a thing named and in doing so pronounce the || its name. And similarly we pronounce, || – for instance || e.g. in an ostensive definition, || – the word “this” as we point || in pointing to the || a thing. And the word “this” and a name can often have the same syntax || stand in the same context: we say “Fetch this”, and also “Fetch Paul”. – But it is precisely one of the characteristic features of a name that its meaning || it is explained by the demonstrative “That || This is N” (or “That || This is called ‘N’”). But do we also explain, “That is called ‘this’”, or perhaps even “This is called ‘this’”? || “This is called ‘this’”? |

This is connected with the

view || idea of naming

as, so to speak, an occult process || an

occult process, as it were.

Naming || The

naming appears

as || like || seems || seems to us

like || seems to us to be a strange

connection of a word with the || between

a word and an object. – 27 ¤ And this || a

strange connection does really take place || really is

made, || –

namely when the philosopher, in order to bring

out || see what the

connection is between a name and

the || a thing named,

stares at an object before

himand at the

same time repeats || , at the same time repeating || ,

repeating a name – or it

may be the word “this” –

over and over again. For the

philosophical problems arise when language

idles. And then

we may imagine well enough || even

imagine || indeed it's easy to imagine that naming

is some remarkable || queer

mental act, as it were a kind of

christening || a kind of christening, as it were, of

the object. And similarly we may || we may then

also say the word “this”

as it

were to the object || to the object, as it

were,

address || addressing

it, || –

a strange use of

this word, that || which probably occurs

only when we are doing || engaged in

philosophy || which is made only when we are

philosophising || which, I think, is never made outside

philosophy. – |

But what gives people the idea of wanting to make

just this word || why should one wish to regard just this word

as a name, when it so obviously isn't a

name? –

Just that || For this very

reason; for

they || we are

inclined to make an

objection || object || raise an objection to

what is generally called

“name” || calling “a name” what is

generally called so; and

the || this

objection can be put in this way || expressed by

saying: that the name really ought to

indicate || stand for something

simple.

And for this one might give the following

reasons || this can be defended as follows:–

A proper name in the ordinary sense would

be || is, for

instance || e.g.,

the word

“Nothung || Excalibur”.

The sword Nothung

consists || consisted

of various parts put together in a

particular || certain way.

If they are put

together differently || in a different way || not put

together in this way then Nothung

doesn't exist.

Now the sentence “Nothung has a sharp

edge” obviously has

meaning || sense,

whether Nothung is still whole or has been smashed to

bits.

Yet if “Nothung” is the name of an

object, then this object doesn't exist any more when

Nothung has been smashed; and since the name

wouldn't have any object

corresponding to it then, it wouldn't have || then has no

object corresponding to it, it hasn't any

meaning.

But then in the sentence, “Nothung has a

sharp edge”, there would

be || is a word that has

no || without a meaning, and

so || therefore the

sentence || “Nothung has a sharp

edge” would be

28

¤ nonsense.

But the sentence || to say this

does have meaning, and so the words of which it consists must

always correspond to something || to the words of which it consists

something must always correspond.

So

that || Therefore in

the || an analysis of the

meaning || sense

◇◇◇ the word “Nothung”

must disappear, and in its

place || instead of it must come words || words must

appear that name || which

stand for || denote

something simple || simple

objects.

And

these || These words we may reasonably call

the real names. |

Let us discuss one point of this argument first of

all || first of all discuss this point of the argument:

namely that the word has no meaning when nothing corresponds to

it. –

It is important to state || note

that the word “meaning” is used ungrammatically

if one uses it || when used to

indicate the thing which

“corresponds” || ‘corresponds’

to the word || the word ‘stands

for’.

This amounts to || is confusing the

meaning of the name with the bearer of the name.

If Paul dies, || is

dead, then we say the bearer of the name is dead,

but no one says || we don't

say the meaning of the name is dead.

And it would be

nonsensical || nonsense || nonsensical

to speak that way || say such a

thing || this, for if the name

had ceased to have meaning, then it

would have no meaning to say,

“Paul has died || is

dead”. |

In (19) we introduced proper names into

our language (11).

Now suppose the tool with the name (α)

is || were || had

been broken.

A doesn't know this, and gives B the

sign (α): has this sign a meaning

now, or has it none || hasn't

it?

–

What

is || What's B supposed to do when he

receives this sign? –

We have made no agreement about this.

You might ask, what will he do?

Well, perhaps he will stand there perplexed, or show A the

pieces.

You might say

here, || :

(α) has become meaningless; and this

expression would indicate that there is now no further use for the sign

(α) in our language game

(unless we (were

to) give it a new one).

(α)

might || may also become meaningless

through the fact

that || ifwe, for any reason whatever, || , for some

reason or other, we scratched a different mark on the tool and

didn't use the sign (α) in the game any

more || scratch a sign || mark on the tool and no longer use

the sign (α). –

But we can also imagine 29 ¤ an agreement

according to which, when a tool is broken and A

gives || shows B the sign of

this tool, B has to shake his head as an answer to

him. –

Thisgives, we might say, || , we might say,

gives the command (α) a place in the

language game, even when || if

this || the tool no longer

exists.

And we can

now || now we may say that the sign

(α) has a meaning even when its bearer

ceases || has

ceased to exist. |

We may

For || We may –

for a large class of cases in which the word

“meaning” is used– || , though not for all

cases of its use, – explain this word

thus:

The || the

meaning of a word is its use in the language. And we often || sometimes explain the meaning of a name by pointing to the bearer of it. || its bearer. |

“But, in that game, do

names || signs that

have never been used for a tool have meaning as

well || too || have meaning also which have never been

used for a tool?”

Let's suppose that “X” is such a

sign || mark || sign

and A gives || shows

this sign || it to B.

–

Well, such a sign might be included in the language game, and B

might be supposed, say, to answer it || Such

signs || Signs of this sort may also be embodied in our language

game, and B expected to answer them also by shaking his

head.

One might || may

e.g. imagine this

as || to be a way

the two of them had of amusing

themselves. || of making their work more

pleasant. |

We said that the sentence, “Nothung has a

sharp edge”, has

meaning || sense even

if || when Nothung has

already been broken to pieces.

Now

that || this

is so because in this language game a name is also used

in the absence of its bearer.

But we can imagine a language game with names

(i.e. || that

is, with signs

that || which we should certainly || certainly

should also call

“names”) in which names are

used only in the presence of their bearers.

Suppose, say, that we were watching a surface

on which coloured spots were || are

moving || move about (as on the screen

of || in a cinema).

There are three such spots, which slowly change their shapes

and positions.

Suppose I

had || have

named them “P”,

“Q” and “R” by giving

ostensive definitions.

Our 30 ¤ language

describes the changes of these three, and I say to

you || we use sentences

like, || : “Do

you see how P is contracting now and is approaching

R?”. –

Now in this language these || the

names are supposed to be used as synonyms

for the demonstrative pronoun “this”

together with the pointing to a coloured

spot || (plus pointing to a coloured spot).

If || Thus

if one of the three spots disappears, then I

can't say “P has

disappeared” – any more than I should say “this

has disappeared” – but we might say

rather,

“The || the

letter ‘P’ drops out of use || is

out.”¤

In this language we || you may || can say, a name loses its meaning if || when its bearer ceases to exist, and the words || signs “P”, “Q” and “R” always have something corresponding to them || there is something which correspond to the words “P”, “Q” and “R” as long as they have any meaning – use in the language game – at all. (For in the sentence, “‘P’ drops out of use” || drops out” || is out”, the sign “‘P’” || ‘P’ occurs, but not “P”; and I assume that we do not || don't speak about past occurrences || events, or || or else here || use another || some other mode of expression for it || for them.) In this language game, then, a name cannot || can't cease to have a bearer; only this isn't any advantage || an asset of the language game, || ; for even when it hasn't a bearer a name may have a purpose, use, i.e. meaning || a name can have a purpose, use, i.e. meaning without having a bearer. (Thus || And thusthe name “Odysseus” has meaning for instance.) || , e.g., the name “Odysseus” has meaning.) |

But our || this language game can,

I think, show us a reason why one may

want || might wish to make the demonstrative pronoun || say that the

demonstrative pronoun is a name: for the

demonstrative “this” can never be without

a meaning || bearer.

One might say, || :

“So long as there is a this, then the

word ‘this’ has meaning, no

matter whether this is simple or

complex.” –

But in fact that || this does

not make it a name.

On the contrary, – for we don't use

a name by making a demonstrative gesture, but only explain it || a name

isn't used with a demonstrative gesture, but only

explained by it. |

Socrates (in the Theaetetus): 32

These primary elements were also what Russell's “individuals” were || are also Russell's “individuals”, and my “objects” (Tractatus Logico-philosophicus). |

33

But isn'ta chess board, for instance, || , say, a

chess board obviously and without qualification

complex? –

You are probably || I suppose

you're thinking of its being made

up || composed of 32 white and 32

black squares; || :

– but mightn't you sayfor

instance also || , e.g.,

that it is made up of the colours white, black and the

pattern of the || a net of

squares?

And so, if there are entirely different ways of

looking at it, do you still want to say that the chess board is

“complex” || ‘complex’

without qualification?

The mistake of asking, outside of a particular

game, || : “Is

this object complex?”, is similar to that which a small

boy once made who had to say || to

decide whether the verb in this and that sentence

was || verbs in such & such sentences were used in the

active or in the passive form, and who

then reflected || pondered the

question || now tried to puzzle out whether

for instance the verb “to

sleep” || the verb “to sleep”, for

instance, meant something active or something

passive. The word “complex” (and so the word “simple” also) is one that we use || used by us in innumerable different ways, connected in various ways with one another || each other. (Is the colour of this square in || of the chess board simple, or does it consist of pure white and pure yellow? And is the white simple, or is it made up || composed of the colours of the rainbow? – Is this stretch || line of 2 cm simple, or does it consist of two part stretches || parts of 1 cm each? But why not of a piece 3 cm long || of 3 cm, and a piece of 1 cm added on in a negative sense?) |

To the philosophical

question, || :

“Is the visual image of this tree complex, and what are

its components?”, the right answer

is, || :

“That depends

on || upon what you understand by

‘complex’”.

(And this, of course, is not answering the question, but rejecting

it.) |

Let us apply the method of

chapter || №

(4) to the account in the Theaetetus:

Let || let

us consider a language game for which this account really holds. || is the correct

account.

The language then

serves || Let the language serve to describe

combinations of 34 ¤ coloured

spots || patches on a

surface.

The spots || patches are squares

and make || form a complex like a

chess board.

There are red, green, white and black squares.

The words of the language are (correspondingly):

“r”, “g”,

“w”, “b”, and a sentence is

a string || row of these

words.

They describe an arrangement of coloured squares in the order

The sentence “ r r b g g g r w w” describes then, for instance, an arrangement of this sort:

But I don't know whether I should say that the figure which our sentence describes consists of four elements or of nine. Well, does 35 ¤ that sentence consist of four

letters or of nine? –

And what are its elements: the letter types or the

letters?

And isn't it quite

indifferent || all the same

which we say, if only we avoid misunderstandings in the

particular case? || in the particular case we avoid

misunderstandings? |

But what does it mean, that we can't explain

(i.e. describe) these elements but only name

them?

That || This

might mean, say, that the description of a

complex, if this complex

consisted || consists, in a

limiting case, || (in a limiting case) of only

one element || square, is simply the name of

the coloured square. || This might

mean, say, that when a complex consists, in a limiting case, of only one

square, then its description is simply the name of

the || that coloured square.

We || One might say here – although this easily leads to all sorts of philosophical superstitions – that a sign “r”, or “b || b” etc., may sometimes be a word and sometimes a sentence. But whether it “ || ‘is a word or a sentence” || ’ depends on the situation in which it is uttered or written. If e.g. A has to describe for B complexes of coloured squares and if he uses here the word “r” alone || by itself, then we may say that the word is here a description – a sentence. But if he memorises, say, || e.g. he is memorising the words and their meanings || what they mean, or if he is teaching another || someone else the use of the words and utters them in connection with ostensive teaching || while giving || with the appropriate gesture, then we shall not say that they are sentences here. In this situation the word “r”, for instance, is not a description; you name || are naming an element with it, || : – but it would be strange to say on that account || that's why it would be strange to say here that the element can only be named. Naming and describing, in fact, are not on the same level: naming is a preparation for describing. When you have named something you || Naming || With || In naming something you || we have not || haven't || haven't yet made a move in the language game, – any more than you have || you've made a move in 36 a chess game || chess by

setting a piece || putting a piece on the

board.

We may say: with the naming of a

thing || by giving a thing a name

nothing

has || nothing's yet been done.

It hasn't even || yet a name,

– except in the game.

That || This

is also what Frege meant

by saying that a word has meaning only in its connection

with || the context of a sentence.

|

What is meant by saying of the elements that we can ascribe neither

being nor not-being to them || that we can ascribe neither being nor

not-being to the elements? –

One || We might say

something like this: If everything that we call being or

not-being consists in the fact that connections hold or do

not hold || connections holding or not holding between the

elements, then there is no sense in speaking of the being

(not-being) of an element; just as, if

everything that we call “destroying” consists in

the separating of

elements || tearing elements apart || apart

elements, it has no sense to speak of destroying an